Louis Sansbury – A Hometown Hero

In honor of Black History Month, we share the story of Louis Sansbury, a Springfield resident and former slave, whose compassion for his community in a time of need made him a hero to many.

If you take a drive down Main Street in Springfield, it may seem that not much has changed over the past few decades, even the past 100 years. The businesses that occupy the historic structures come and go, but the buildings remain.

Most of them, anyway.

Nearly 180 years ago, the lot at the corner of Walnut and Main was home to a blacksmith’s shop, owned by a man who might as well have been called the Angel of Springfield.

In 1833, Kentucky was paralyzed with an epidemic of cholera, a bacterial disease spread by drinking contaminated water. It entered the commonwealth in places like Louisville after traveling up the river, then quickly spread elsewhere as residents fled their affected homes and communities. Eventually, the deadly disease made its way to Springfield, then home to around 620 people. In her book, It Happened in Kentucky, Mimi O’Malley writes that in the first day of the outbreak in the city, three people contracted the disease and died. The next day, five more died, and 10 on the third day. By the end of 1833, it’s believed that 80 people had died from the illness. Facing such a fatal illness, it’s no surprise the town’s residents quickly fled, which brings us to the subject of this story.

Louis Sansbury was a 27-year old man enslaved by George Sansbury, a hotel owner. As the disease quickly spread throughout the area, George prepared to flee the disease-stricken community, giving Louis the key to his hotel and asking him to watch over it while he was gone. Soon, more of the town’s business owners and shopkeepers also fled, leaving their keys in the hands of Sansbury, who promised to watch over their shops as well.

Louis kept his word, taking care of the shops left to him, as well as caring for the sick and dying residents who stayed behind. He was not alone in his mission of caring for those around him. A cook named Matilda Sims also stayed in Springfield, helping Louis feed and care for the sick.

To this day, it is not known why Louis and Matilda did not become infected with cholera themselves, or why Louis did not simply ignore the instructions of his enslaver and flee north to freedom.

The book Pioneer History of Washington County, Kentucky, written by former community historian Orval W. Baylor, as well as the book by O’Malley, offer insights into how Louis and Matilda cared for the town. When death struck, Louis and Matilda would prepare the bodies for burial, placing them in graves that Louis had dug on the sides of the road leading to Springfield’s Cemetery Hill.

His compassion and care made him a local hero to the residents of Springfield. The town showed their gratitude to Louis in 1845. After George’s death, the town purchased Louis’ freedom, and helped him establish his own businesses—first, a stable and livery, which they stocked with horses, and eventually a blacksmith shop at the same location.

According to a display at the Washington County Public Library, Louis was deeded a large house on High Street in 1853 for $75. The house still stands today, currently undergoing renovations.

Louis’ work tending to cholera patients would not be completed, as a second wave of the deadly disease hit Springfield in 1854. Just as he had done 21 years before, Louis stayed in Springfield as others fled.

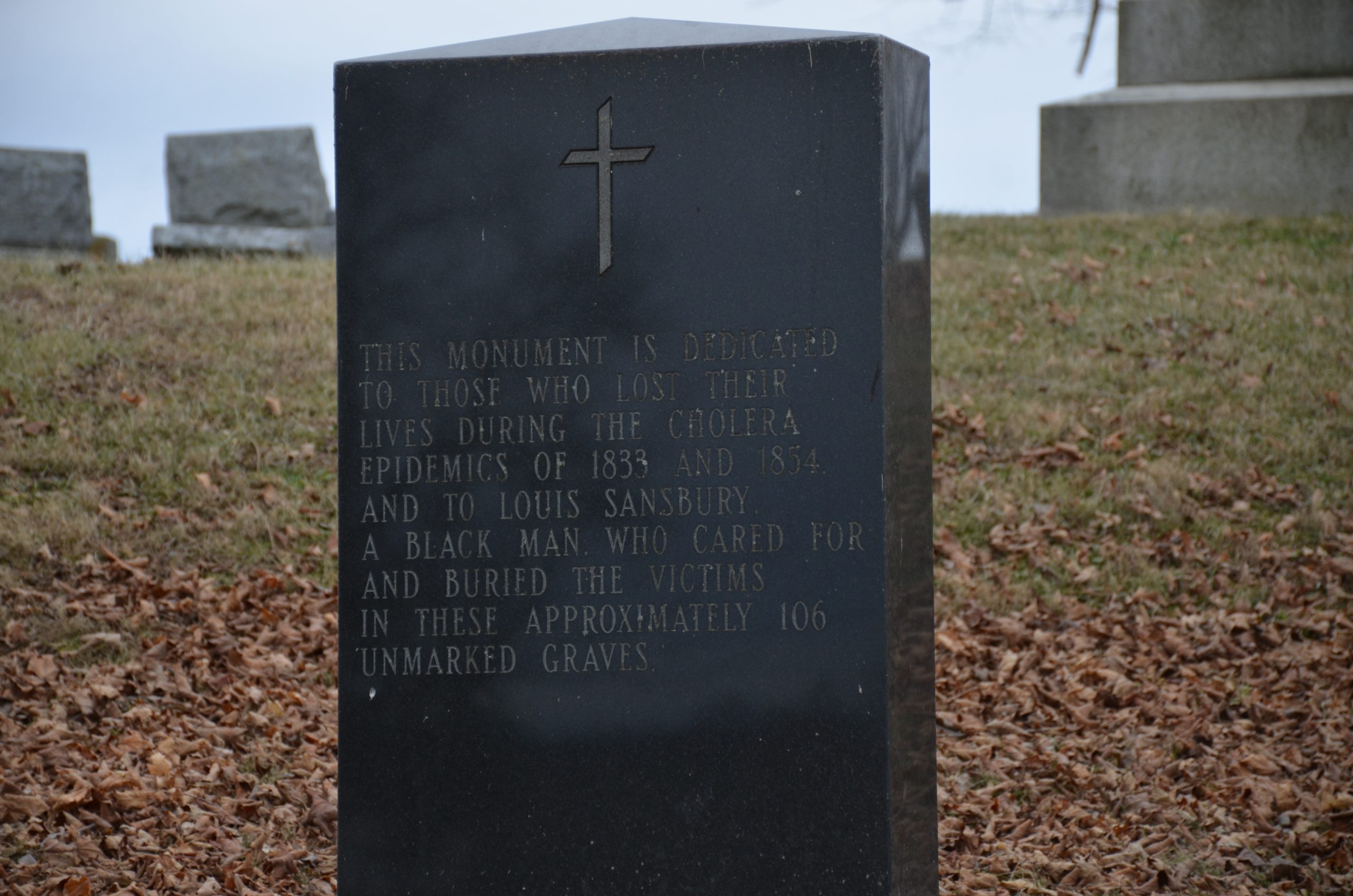

Louis Sansbury died on April 12, 1861, a 55-year-old former slave turned free man. His care of the sick and dying residents of Springfield through two cholera outbreaks is remembered in several places around town: a drawing featured at the library, a plaque secured to a brick wall near the site of his former business and a monument on Cemetery Hill with this inscription: “This monument is dedicated to those who lost their lives during the cholera epidemics of 1833 and 1854, and Louis Sansbury, a black man who cared for and buried the victims in these approximately 106 unmarked graves.”